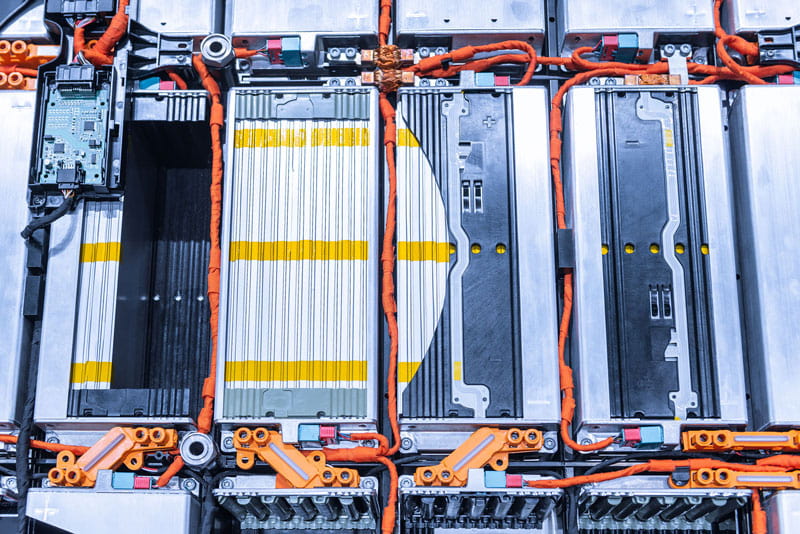

Like many in the battery industry, I’m following the developments of the Chevy Bolt recall closely. Unlike other recent battery recalls tied to onboard software-based, battery management system (BMS) issues¹, the anode tear and the folded separator issue the Bolt is experiencing are both tied to manufacturing problems². Analysts have already characterized this as a perfect storm; namely, an infrequent defect involving the alignment/folding of the separator and potential tears in the anode — both critical components — inside the 288 lithium-ion pouch cells that make up the Bolt’s battery pack.

So just how big of a problem is this? It is now reported that the defect occurred across multiple LG factories and possibly dates back to the very beginning of the Bolt’s production run in December 2016. The global fleet now totals more than 140,000 vehicles, with some 90% sold in the United States and Canada. That means these defects potentially span a massive population of 40 million pouch cells!

A “perfect storm” indeed. Ten vehicles have already caught on fire. There are an estimated $1B+ of remediation and warranty costs, not to mention credibility issues for both GM and LG. This is especially true when you consider that both of these companies recently committed billions of dollars to build two jointly operated battery factories in the United States.

The question that is surely being asked by LG and GM executives, and many others is: “Why recall every vehicle, instead of the ones with suspect cells and batteries?” The answer is simple. Like many battery OEMs and integrators, Chevy and LG cannot easily reach into their supply chain and pinpoint the potentially affected battery cells by serial number, and in turn, trace those to the corresponding VINs (Vehicle Identification Numbers). Traceability is a very real problem in the battery industry, especially when you consider the complex supply chain that spans multiple sub-suppliers, multiple factories, and multiple regions. At Peaxy, we consistently see this “battery chain of custody” problem across battery OEMs, battery integrators and battery operators.

Whereas publicly available details on the anode tear issue are unknown, the separator/separator folding issue is reportedly tied to possible assembly robot calibration errors. You can well imagine the small army of supply chain specialists along with MES/IT/QC and shop floor technicians trying to thread the Bolt’s battery data value chain. If you haven’t threaded the data (by battery serial number) ahead of time, it is extremely costly and difficult to do after the fact. The work involves painstakingly identifying which assembly robots or stations exhibited calibration issues, and which specific battery cells those robots handled to narrow down the suspect cells and suspect VINs.

I can imagine that GM and LG executives are also asking why the tens of millions of dollars in ERP and MES software investment are unable to provide that level of traceability. The answer — at a high level — is that those systems don’t thread data down to the battery or cell serial number. Why can’t these mission-critical systems used during battery manufacturing follow the trail of bread crumbs back to the specific battery cell serial number? The answer is that it’s very difficult to do with software that wasn’t designed for that purpose. The question presupposes that the data may only be useful at some potential time in the future. In other words, it requires foresight, deliberate planning, investment and carefully orchestrated execution. But given the fire and safety risk, you have to wonder why GM and LG aren’t insisting on threaded battery data throughout the supply chain.

Establishing a chain of custody during battery manufacture involves coordinated efforts, traverses shop floor systems (MES), sourcing systems (ERP), formation testing, and demands traceability from VIN to battery cell to the individual assembly robot. Since multiple systems are involved, there is no single data source, and what data there is may be inadequately maintained, stored in various non-compatible formats, and lack a standard nomenclature, among other potential issues. It’s messy and requires software that’s fit for the purpose of threading all that data over the battery lifecycle.

When we work with battery customers, the first thing we talk about is the state of their data — where is it, who owns it, and how does it get updated? Only until we understand the data landscape can we begin to piece together a strategy for creating a single source of truth that spans the entire manufacturing process, with critical traceability down to the individual cell/battery serial number. The good news is once a single normalized and continuously updated data thread is established for battery data, it can also be used to route data through machine-learning enabled anomaly detection algorithms to alert operators of potential faults.

If you plan ahead, the costs are extremely reasonable. A similar data threading approach would have — undoubtedly — been extremely useful for diagnosing and limiting the recall to a significantly smaller population of VINs in the case of the Chevy Bolt.

[1]: https://www.motortrend.com/news/ford-mustang-mach-e-charging-issue-bricking/